A meditation on

The Scale (2019)

Distorted perception, invisible shame and toxic aesthetic norms

⏱︎ 8 minute read

TL;DR

The Scale is a physical expression of body dysmorphia, reflecting the distorted self-perception caused by the condition. The piece also critiques the shame-based systems that reinforce harmful body ideals.

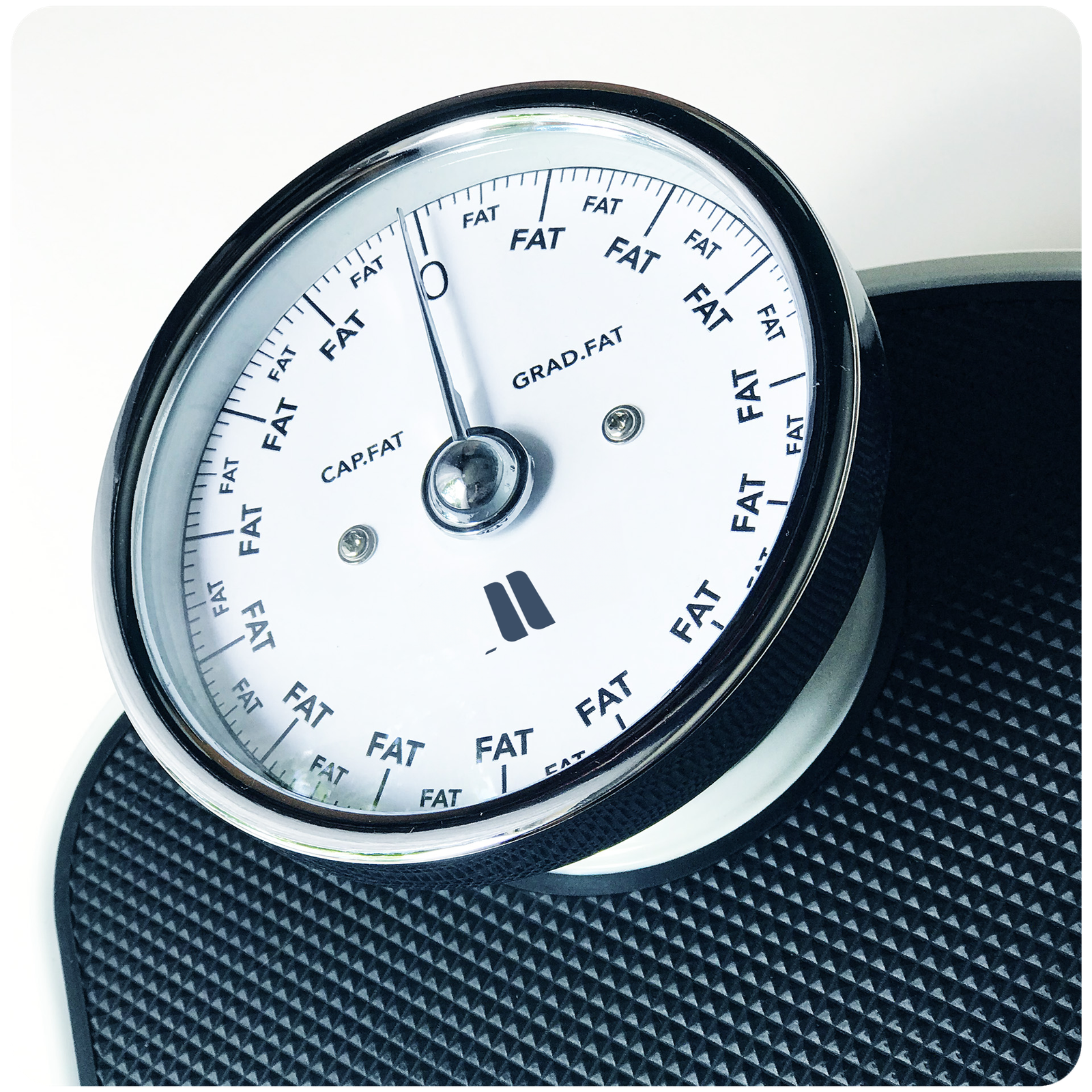

Material description

An analogue, fully functional bathroom scale with all numerical weight markers replaced by the word fat. The dial and needle remain operational but no longer display standard units of measurement.

Fundamental idea

To embody the lived experience of body dysmorphia and expose the cultural and corporate mechanisms that distort our self-image for profit.

Philosophical questions

What happens when self-worth is measured by appearance or a scale? And who profits when we believe we’re never enough?

Context

I spent most of my twenties obsessing over my weight. Even with a BMI of 24, I still saw myself as fat. I became addicted to my scales, ritualising a daily judgement I couldn’t escape. Eventually, I realised I wasn’t just struggling with self-image, I was dealing with Body Dysmorphic Disorder: a mental health condition where perception detaches from reality.

With The Scale, I aim to materialise a condition that’s often difficult to describe, especially to those who’ve never experienced it. Every number is replaced with the word fat, because no matter what the actual reading was, that’s what I saw.

The piece speaks to the hidden, repetitive feedback loop of body dysmorphia. It’s also a reflection on a broader societal distortion, one shaped by media, marketing, and cultural obsession with perfection. It asks how do we measure our self worth in a world where the question “Are you beach body ready?” becomes less about health and more about conformity.

“Shame is the most powerful, master emotion. It’s the fear that we’re not good enough.”

Background

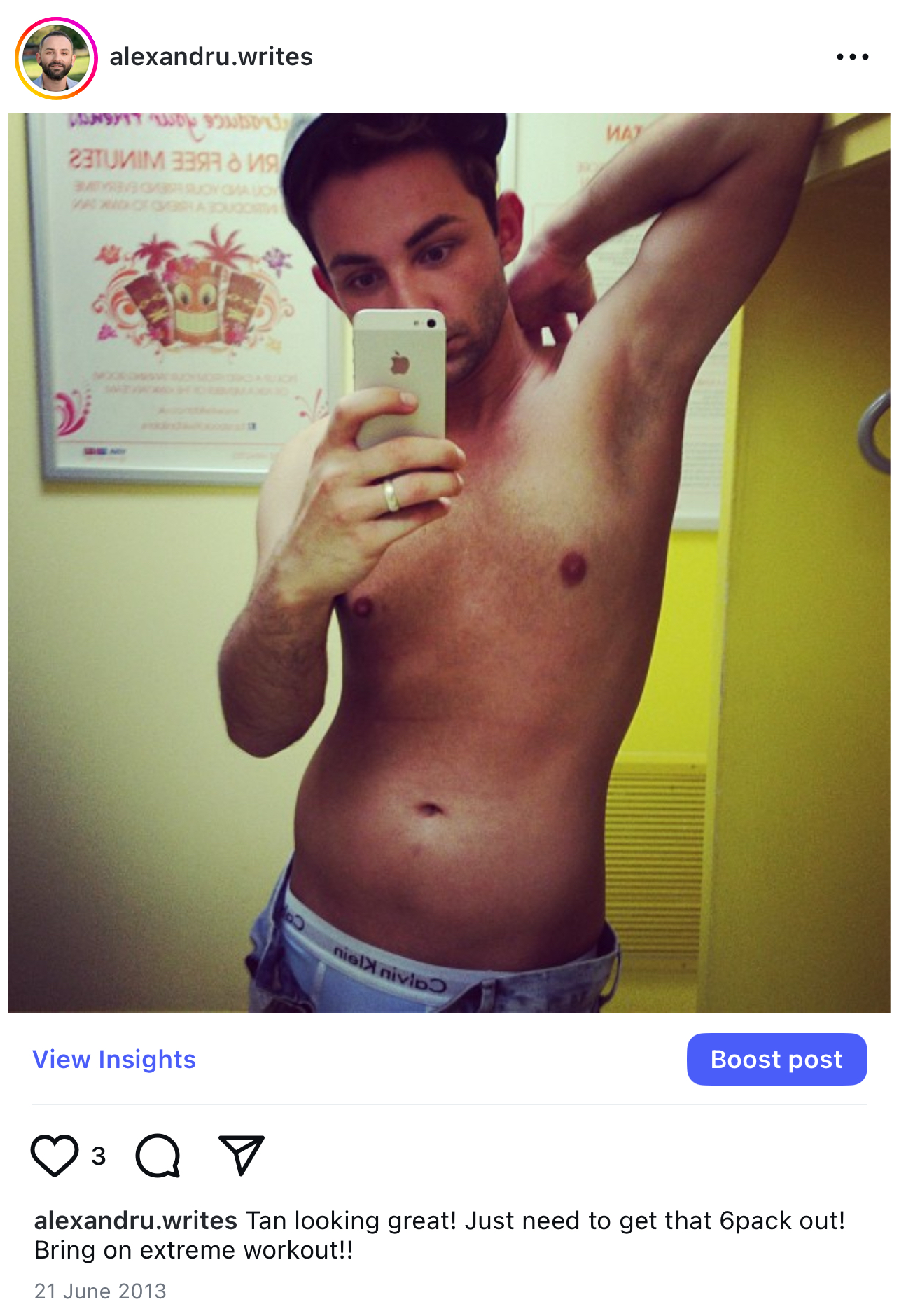

Just look at this boy. I just want to reach into that moment and tell him “it will all be OK”. He was so lost and in a constant struggle to fit in. It’s tough making friends as a first generation immigrant, and when you’re also running away from and not dealing with childhood abuse and trauma, you usually meet all the wrong people. But throughout the foes and struggles, I still admire his relentless mandate to never settle for anything less than what he can achieve, to borrow some wisdom from Jane Fonda.

I took this picture at a tanning salon. I was 23. I had to dig deep in my archival photos to find it. I was 23. I remember sucking in my belly and raising my arm so that my tiny biceps would show. I framed myself in the mirror by the sun bed and thought “that may work”. I knew it wasn’t good enough. It never was. I then posted that picture on instagram. Not much in the way of a response; perhaps not much of a thirst trap. When I got home, I tortured myself with the Insanity workout (if you never heard of it, it’s basically HIIT). I was hungry for acceptance, for care.

In the following days, I was talking to one of my housemates and I mentioned to her that I thought I was fat, whilst grabbing the flabby skin at the base of my torso. Her reaction: “Alix! You are not fat!”. I dismissed her immediately. In my head, it wasn’t even a debate. It wasn’t good enough. It wasn’t long before I started hearing whispers about Body Dysmorphia. I started reading, and suddenly, something clicked. I remember the realisation vividly: “This is me! This is what’s happening”. That was a powerful realisation as it marked the beginning of my healing process.

At some point, around 26 or 27 years of age, I stumbled over Brené Brown’s TED Talk on shame and vulnerability, and ever since I have been a loyal student of her work. From The Gifts of Imperfection to the remarkable Atlas of the Heart, I was totally captivated by her deep understanding of the human condition.

“Perfectionism is a self-destructive and addictive belief system that fuels this primary thought: If I look perfect, live perfectly, and do everything perfectly, I can avoid or minimize the painful feelings of shame, judgment, and blame.”

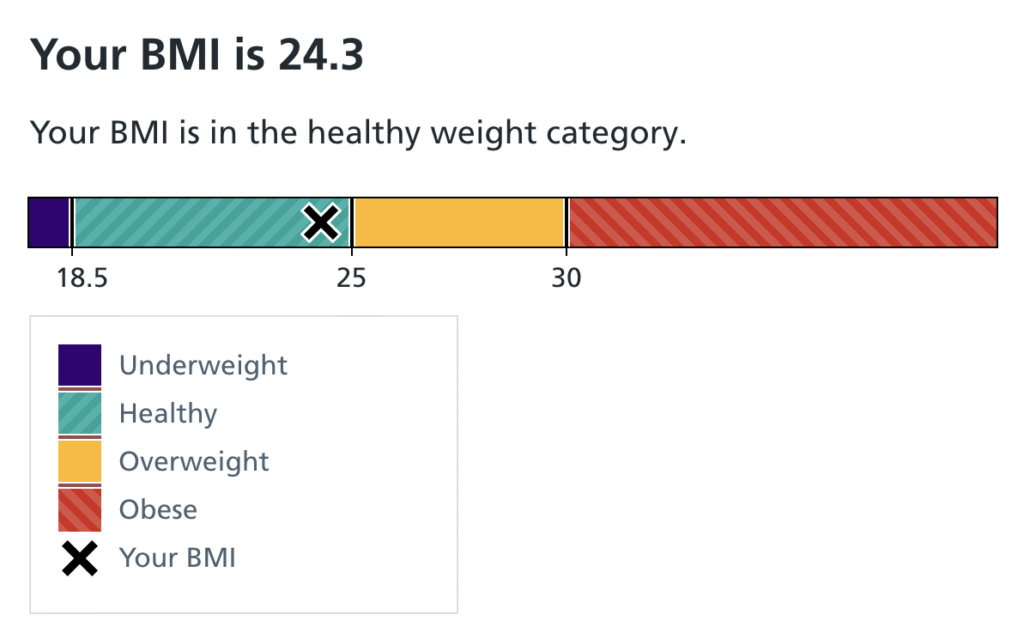

The shame of not looking good enough has followed me for decades. I was fat-shamed as a child. That abuse and bullying carries on to this day. At some point, in my early thirties, I visited my family and nearly everyone commented on my size. I don’t have many full-body photos from that time; most were cropped above the neck. You’ll have to take my word that a 1.72m (5ft6), 70kg (11 stone) adult is not fat. The NHS classifies a BMI of 24 as within the normal range (screenshot below, left) although I can’t imagine why it’s so close to the limit of being overweight. More on the topic of BM’s another time.

2013 – 23 years old

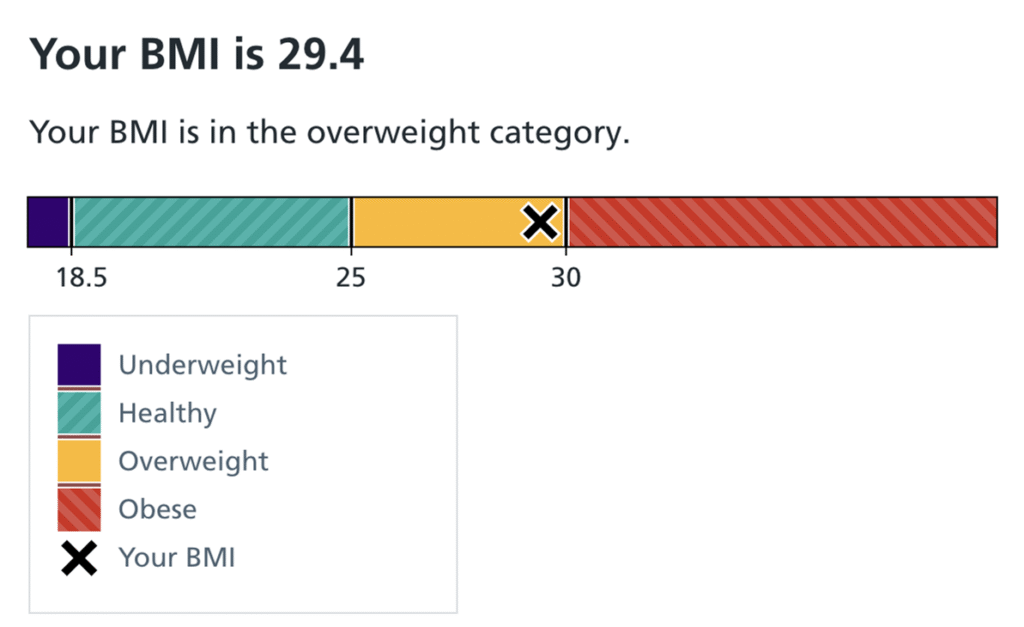

2023 – 33 years old

At 33, with a BMI of nearly 30 (screenshot above, right) I am on the cusp of obesity. A sad reality for many who struggle with BDD is that we never end up in our ideal shape. I developed an unhealthy relationship with food that has stood the test of time and therapy, unfortunately. Coupled with poverty and scarcity, it’s the perfect shitstorm. Even after all the work I’ve done in therapy, I still sometimes see myself through the same distorted lens – luckily, only when I look in the mirror. The last remaining relic. I’ve come a long way since then. Therapy and support has yielded me a better perspective. Now I draw my self worth from the love and care that I surround myself with. Difficult goodbyes have been said to people and old habits in order to make room for the right ones.

I made The Scale so that people who don’t live with Body Dysmorphia could experience the repetition, the distortion and the absurdity that once used to dominate my life. I also made it so that others could point to it and say “this is how I feel”, and maybe for a moment they will feel less alone.

Philosophical Treatment

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a mental health condition in which a person becomes obsessed with perceived flaws in their appearance, flaws often invisible to others. It’s complex. Shame, perfectionism, trauma, neurobiology, and environment all feed into it.

The Scale is an object that confronts this condition, raising awareness of how BDD distorts reality and undermines identity. But the piece also gestures beyond the individual. It asks: how did we get here?

Over the past decade, body shame has been amplified by culture and technology. From protein-shake patriarchy to “Are you beach-body ready?” campaigns to the quiet violence of algorithmic manipulation, we’ve normalised a way of being that feeds on inadequacy.

“If a teen deleted a selfie, the algorithm would automatically push ads for things like beauty products, filters, and weight loss.”

Sarah Wynn-Williams, former Meta executive turned whistleblower

It’s a closed loop: comparison leads to shame, shame leads to consumption, and consumption funds the system that created the comparison. Beautifying filters, influencer diets, weight-loss ads aimed at teens—these aren’t accidents. They’re symptoms of a market that capitalises on shame.

And it’s not new. Shame has been a sales tool since trade began. Cars for (some) men = status. Weight loss for (some) women = acceptance. Everyone has felt the sharp edge of this narrative. No one escapes it untouched.

The Scale speaks to BDD, but also to something wider. It asks: How are we okay with this? How are we not more furious? And maybe most urgent: If you’re ignoring it to protect your own mental health, what happens when you just can’t anymore?