The mind creates both the beauty we long for and the pain we try to outrun. It takes courage to face all of it. That courage is a skill, and like all skills, it can be learned. My work is an invitation to begin.

The world needs it.

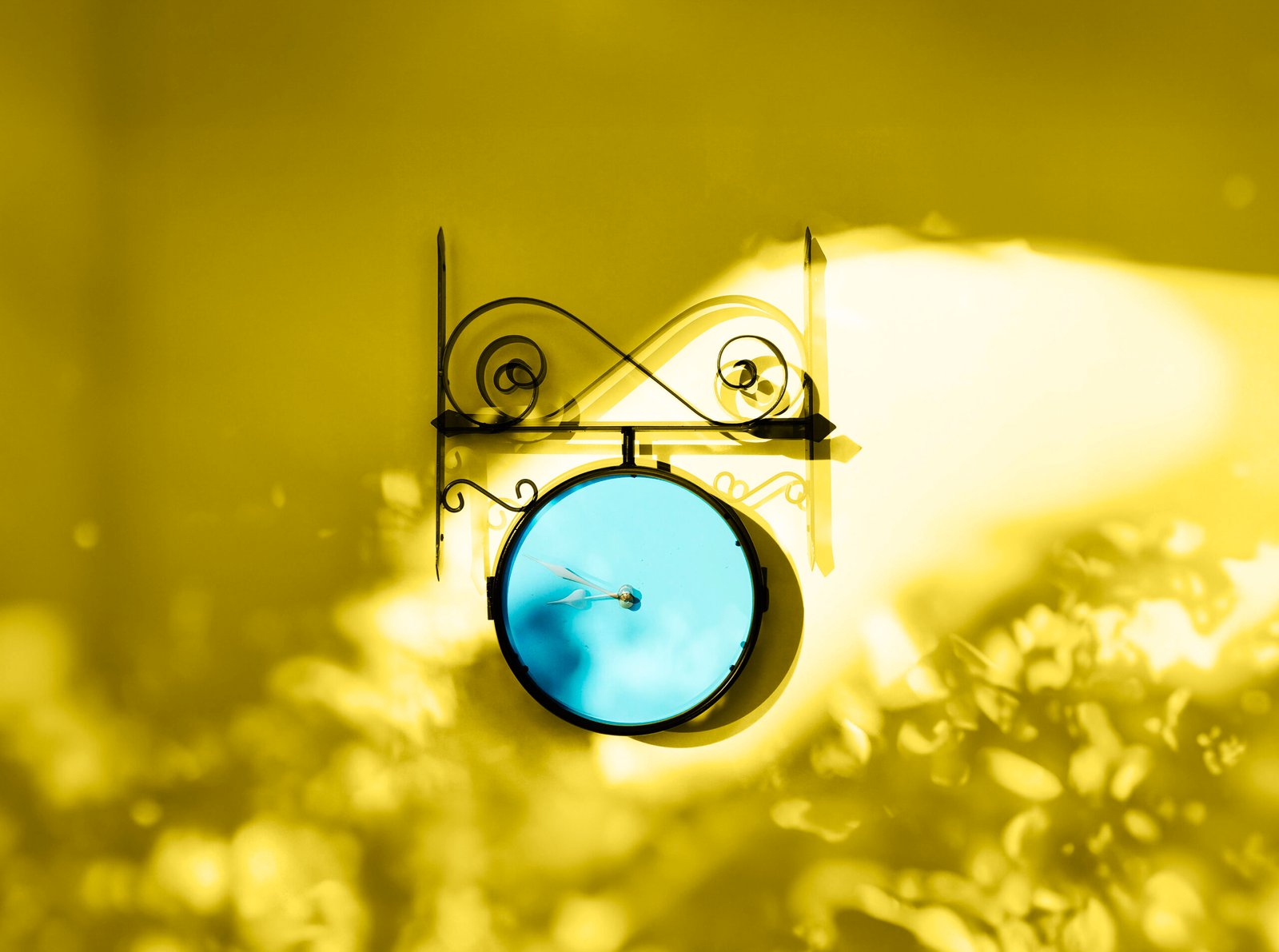

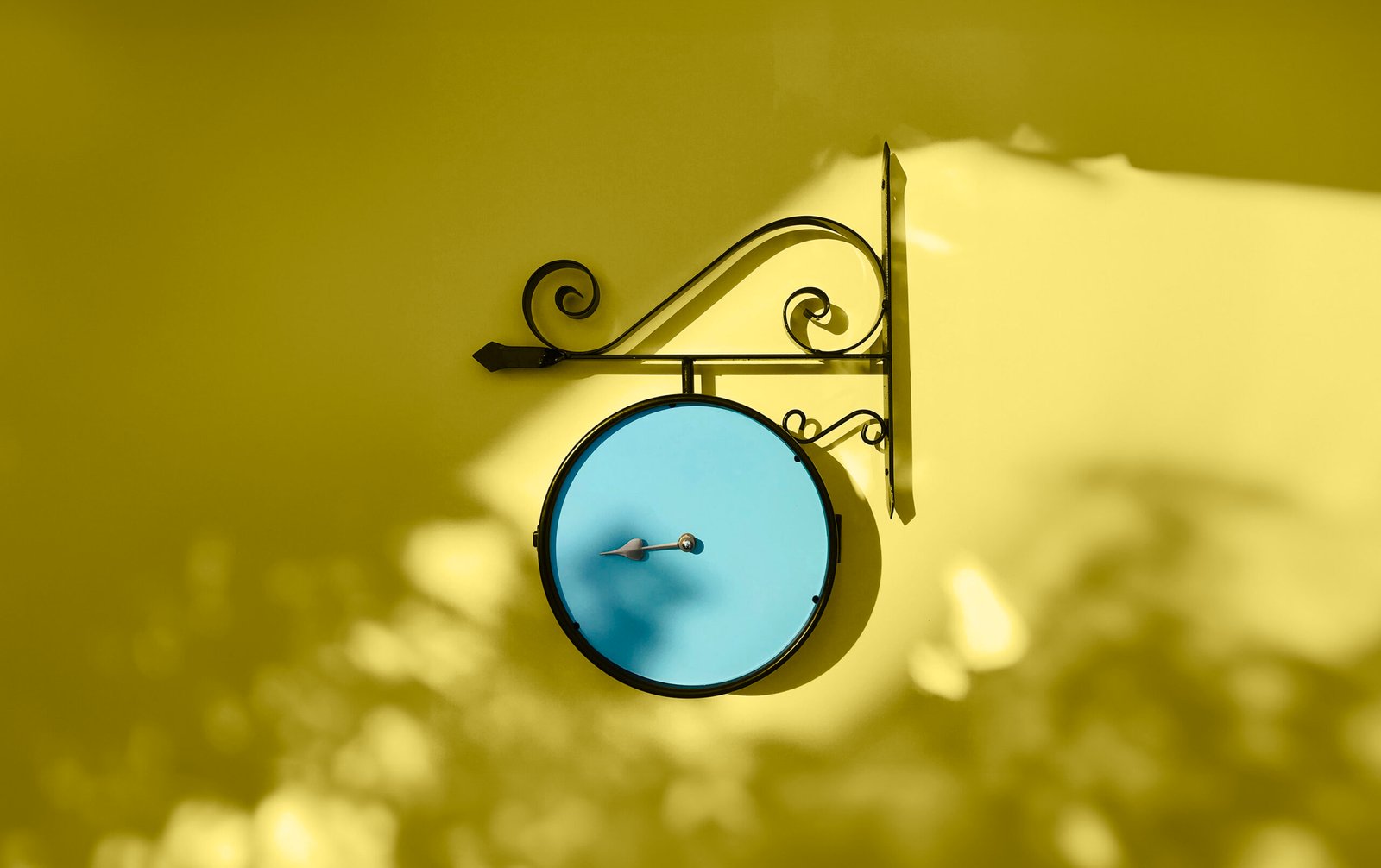

Slide to reveal the two sides of the clock (minutes + hours)

A meditation on

The Clock (2019)

Social norms, oppression, division, and the myth of gendered traits

⏱︎ 19 minute read

TL;DR

A non-binary artist’s perspective on the illusion of gendered traits, using a two faced clock to expose the dangers of dividing what are human traits into masculine and feminine.

Material description

A two-sided, 19th-century-style platform clock, modified to display only the hour hand on one face and only the minute hand on the other, with all numerals removed.

Fundamental idea

The materialisation of the division of human traits as either masculine or feminine

Philosophical questions

If human traits are universal, why do we divide them by gender? What are the consequences of this division?

Context

In terms of gender, I identify as a non-binary person. At no point have I ever felt like either a man or a woman. I simply don’t live that way in my mind, although I look and sound like what most would agree is a cisgender male. Moreover, dividing human traits into masculine and feminine has always felt strange and nonsensical.

I take issue with the standard and often esoteric idea that certain traits are inherently male or female. I just don’t buy it. It’s more likely and more plausible that we live with both dimensions within us. We are born with different components and chemistries that are shaped by our environment. This is not about gender ideology but about instruments we create to achieve certain goals. What is the goal here then? That’s what this piece exposes. Dividing traits by gender isn’t just inaccurate, it’s dangerous as well.

There’s no such trait that is exclusively masculine or feminine. In the traditional sense, men can be examples of so-called feminine traits such as tenderness, love, and compassion. We know this from common sense, so why do we bother?

“All sorts of things which we believe to be real are as a matter of fact conventions. Now, you know very well that you cannot tie up a parcel with the equator because the equator is an imaginary line. And in exactly the same way, time, clock time, is an imaginary way of dividing motion, of measuring motion. But it so happens that these social institutions become so convenient and so useful that we start to mistake them for the real world, and that can lead us into an enormous amount of confusion. The same sort of confusion from which you would suffer if, for example, you started eating the menu instead of the dinner. And we must recognise that a great many things, all of which we take for solid reality, are in fact social institutions. They are conventions.”

Alan Watts on the Philosophy of the Tao

Background

Audio transcribed from Alan Watts’s talk on Carl Jung – two personal favourites of mine.

“One of the basic things which all social rules of convention conceal is what I would call the fundamental fellowship between yes and no, say in the Chinese symbolism of the positive and the negative, the yang and the yin. You’ve seen that symbol of them together, like two interlocked fishes. Well, the great game, the whole pretence of most society is that these two fishes are involved in a battle; there’s the up fish and the down fish; the good fish and the bad fish; and they’re out for a killing; and the white fish is one of these days going to slay the black fish; but when you see into it clearly you realise that the white fish and the black fish go together; they’re twins; they’re not fighting each other, they’re dancing with each other, though it is a difficult thing to realise in a set of rules in which yes and no are the basic and formally opposed terms.

When it is explicit in a set of rules that yes and no, or positive and negative, are the fundamental principles, it is implicit but not explicit that there is this fundamental bondage or fellowship between the two. The fear is, you see, that if people find that out they won’t play the game anymore. Suppose a certain social group finds out that its enemy group, which it’s supposed to fight, is really symbiotic to it; that is to say the enemy group fosters the survival of the group by pruning its population. We’d never do to admit that; we’d never, never do to admit the advantage (brought on by) the enemy. Just as George Orwell pointed out in his fantasy of the future, 1984, a dictatorial government has to have an enemy, and if there isn’t one, it has to invent one. By these means, by having something to fight, you see, having something to compete against, the energy of society to go on doing its job is stirred up. And what the buddha or bodhisattva type of person fundamentally is one who’s seen through that, who doesn’t have to be stirred up by hatred and fear and competition to go on with the game of life.”

This text resonates with me profoundly. I think Alan Watts had a great understanding of Carl Jung’s philosophical thinking whilst also being able to expand on Jung’s concepts for a greater understanding. The fundamental battle between good and evil is mostly misunderstood, in the sense that it does not exist. To quote Watts further, referring to one of Jung’s lecture texts:

“(Jung is) trying to heal this insanity from which our culture in particular has suffered, of thinking that a human being could become hale, healthy and holy by being divided against himself in inner conflict, paralleling the idea of a cosmic conflict between an absolute good and an absolute evil which cannot be reduced to any prior or underlying unity. In other words, our rage, and our very proper rage, against evil things that occur in this world must not overstep itself. For if we require as a justification for our rage a fundamental and metaphysical division between good and evil, we have an insane and in a certain sense a schizophrenic universe, of which no sense whatsoever could ever be made.”

When it comes to gender specific traits, as well as the current gender identity conflicts, it is not a fight between good and evil. It is a fight for dominance, rooted in fear and taking advantage of a great misunderstanding amongst people, with the intent to control and oppress. Therein lies the true danger.

Philosophical Treatment

In this art piece, time is separated into minutes and hours by using each of the two faces of the clock; one absurd division drawing attention to another. There is much to be said about time, both as a concept and as an instrument, as is the case with gender. There are instances where knowing or speaking exclusively of the hour is relevant: it’s noon; I have a nine to five job. Similarly, speaking exclusively about the minute is often relevant: the team secured their goal at minute sixty three of the game; it will only take a minute. When it comes to such expressions, I draw a parallel between them and certain expressions we use when it comes to gender: act like a man; the characteristic caring nature of women. This is mostly a linguistic argument, yet I find it indicative of how differently we think about time and gender. Namely, we think about time as a whole, yet we don’t think of gender or gender traits as a whole – why? Is it because we don’t think about time as a concept but rather as an instrument, whilst viewing gender (too often confused with biological sex) solely as a concept or as a fact? Is this confusion preventing us from seeing gender as an instrument too? And if so, what purpose does it serve?

The harder I tried to make sense of it, the more it made less sense. Nobody has ever offered a coherent list of traits that apply exclusively to men. It’s always the same tired list: strength, leadership, independence, resilience, assertiveness, stoicism, competitiveness, protectiveness. Couldn’t this be said about women? Of course it can. Conversely, so-called feminine traits, as expressed by some people, are empathy, nurturing, sensitivity, cooperation, emotional intelligence, gentleness, patience, and adaptability. The strongest person who has ever walked the earth, irrespective of sex or gender, has walked with these traits in their nature. At least, if we are to be true to the real meaning of strength.

I hear the phrase “dismantle the patriarchy” often, and that conversation matters, although it is too often misunderstood. The goal is to address toxic masculinity, which is this abstract yet misguided and dangerous concept of what a man is. Yet, I grew up in a matriarchy. In my hometown, women were in charge of the social norms. It may shock you to know that it almost perfectly resembled the same kind of patriarchal oppression and control we are fighting against now. Indeed, the women leaders of my childhood embodied the same toxic masculinity we talk about today. I saw firsthand that flipping the power balance to women doesn’t solve the problem. Matriarchies and patriarchies both enforce toxic and dangerous norms with the intent to control people. If you think all women have somehow inherited these traits that make them women, I would encourage you to go to my hometown and seek out the spineless women leaders of my upbringing. If you spoke to these women, you’d think you’d stepped into an episode of Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror.

As time unwinds, the gender construct collapses. The original clock served a clear purpose; this manipulated clock, like gendered traits, is dysfunctional. It splits what should be whole. I will not draw the rather inescapable conclusion that everyone who identifies with traditional gender norms is suffering from some sort of delusion imposed by society. I have no intention to invalidate anyone’s experience. Identity is deeply personal, and I honour yours as I honour mine. What I will say is this: the social norms around gender are not designed to celebrate difference. Aside from some debatable linguistic traditions, the act of gendering is designed to divide people for the benefit of one group over another, and that is a dangerous game to play. It’s a hurtful game, one that confuses, manipulates, and ultimately (drumroll please) coerces people into submission. A tale as old as time.

Submission has little to do with safeguarding or with keeping a society going in a structured way – how could it? Especially when it insists on division and rejects outright our natural differences of being. It doesn’t just affect women; it affects men too. It is impossible to live under this system and not be shaped by it and wounded by it. Many benefit greatly from its rules and they, in turn, become the guardians of the gender segregation. Those who cling to this phantasm, this self-imposed division, are themselves trapped by a system that doesn’t truly serve them and never has.

The conversations we are now having around trans rights and gender norms are quite obviously another attempt at control by segregation, and it’s heartbreaking to watch. Many who claim that trans women are a threat to women often hold deeper agendas. Seldom does the conversation turn to trans men, and that’s a very important observation to mention. Many cultural and media narratives have historically been more focused on trans women, often due to deep-rooted societal notions about gender and femininity. Trans women challenge traditional ideas of what it means to be a woman, which can provoke more backlash in a society that often polices women’s identities and bodies more strictly. Additionally, trans women’s visibility in certain public spaces, like sports or women’s restrooms, has been a focal point of debate. Trans men, while also facing significant challenges, might not be as frequently targeted in these cultural conflicts because their experiences don’t always fit as neatly into the prevailing narratives that the media and culture wars tend to focus on.

My hope is to bring awareness to this gender trait division, as an instrument of control. This is important to acknowledge because it informs how we think about gender and subsequently enforce this thinking. I hope to shift the focus from the abstract concept to the instrument of control. From the perspective of someone who looks and is treated as a cisgender man, yet non-binary in nature, I believe we have something important to gain from dismantling this narrative: our true identity as individuals.

What remains unsaid (for now)

There is so much more I would have liked to expand on in this treatment. Toxic masculinity, human traits, fear, intersectionality, and so on. This is a complex topic, and one that deserves far more space than I can give it here.

I’m not a researcher or a philosopher in the academic sense. My role is to observe and express concepts through art in order to reflect a perspective into this world. I hope my art is a conversation starter, and that many of you will be empowered to understand the games we play in life. As Brené Brown puts it: “I’m not here to be right. I’m here to get it right.”

To be clear, I am speaking of gender as a concept, not as physical descriptors of people and their genitals. The obsession with genitals is yet another, peculiar at best, attempt to control and segregate.

Trans women are women, and I stand with the trans community as a whole. I do not omit intersex people from this argument out of negligence. I positioned my art piece and its philosophical treatment on the binary solely to reflect the usual segregation of gender traits.

Brené Brown’s Atlas of the Heart explores emotions and traits without assigning them to genders. Harriet Lerner’s The Dance of Fear offers deep insights into how fear shapes behaviour — insights that are painfully relevant to today’s anti-trans rhetoric. Intersectional feminism is another field I continue to research because it reveals that gender is always shaped by race, geography, class, and sexuality, and any serious conversation about gender must recognise this nuance.

For more on gender and oppression, I wholeheartedly recommend Abigail Thorn’s Philosophy Tube. Did you know some early suffragettes were fascists, and that their fight for “women’s rights” was often explicitly about white women’s rights? It’s hard to pick a favourite video from Thorn’s channel, but if I absolutely had to, I would recommend this one.

I leave you with this:

“I’m about to tell you a secret. The closet is not just for gay people; it’s just that gay people were honest that we were closeted. Everybody’s closet and everybody plays pretend; they all walk around saying “I am” even though they have no idea who they are. What they’re often saying is “I wanna make you feel comfortable so I’m going to contort myself into who I think that you want me to be”. That is a form of injury that I, as a poet, could spend eons trying to write and never articulate; the pain of feeling like the only way you can belong is by betraying yourself and shapeshifting, knowing that that love is dependent on your self-disappearance. The reason that trans people like me inspire so much envy – which is a synonym for transphobia – is because people look at us and they say “what do you mean you get to be free now? I thought we had to play pretend. I thought we had to play hide and seek our entire lives”. And trans people have the moral fortitude and clarity to look at the world and say no.”

Alok Vaid-Menon

Watch the source video on instagram.